By Dan Duffield | Sport Science Consultant | Fusion Sport

When athlete data management first started, wearables were still in their infancy, so there was a limited amount of information available. Due to restricted connectivity, this had to be collected and entered manually. Then as devices advanced and diversified, the amount of data greatly increased, and the main challenge became centralizing it on a single platform. Now we’re entering a third stage, in which the onus is on interpreting the data and making it actionable. In this article, we’ll explore some ways to achieve this. These include transitioning from a reductionist approach to an emergent/collaborative one and formulating the right questions before looking to data for answers that can improve athlete performance and wellbeing.

THE PITFALLS OF INFORMATION SILOS

When a specialist or team of experts in a certain field gathers information pertaining to their specific areas and wants to hold onto it, a silo is created. The more silos there are within an organization, the more the proverbial left hand doesn’t know what the right hand is doing and the less useful interdepartmental collaboration there is. In his book Silos, Politics and Turf Wars, Patrick Lencioni wrote, “Silos – and the turf wars they enable – devastate organizations. They waste resources, kill productivity, and jeopardize the achievement of goals.”[i]

In the case of sports, a goal that can be compromised by silos is preparing athletes to be at their best physically, mentally, and emotionally on game day. In one study, 88 percent of athletic department employees at over 400 NCAA Division I schools reported that silos existed in their organization, leading to the destruction of trust, hindrance of communication, and the fostering of complacency.[ii] Swimming coach Wayne Goldsmith asserted that the main reason for siloing in college sports is that “Universities teach the reductionist approach to sports science through their teaching structures, i.e. sports physiology or sport biomechanics or sport psychology or sport nutrition: the so called “faculty” or “silo” approach to sports science.”[iii] He went on to suggest that each of these disciplines’ practitioners approach their research and its application through a zoomed-in lens, leading to reductionist thinking and practices.

So while the range of athlete data has become wider, its analysis and interpretation is arguably too narrow. As Goldsmith suggested, you could have a nutritionist looking at one data set, an exercise physiologist examining another, and a sports psychologist evaluating a third. And then all three (plus the other specialties that often exist in pro and college team structures) trying to implement disparate strategies with the athletes they serve. And while one nutritionist is usually comfortable talking to a peer, they might find it harder to join the dots with others whose job descriptions and mandates they’re not as familiar with. This lack of communication between job roles merely serves to further reinforce silos, encourage reductionism, and prevent insights gleaned from athlete data from making meaningful changes in athlete preparation.

BREAKING DOWN WALLS WITH AN INTERDISCIPLINARY APPROACH

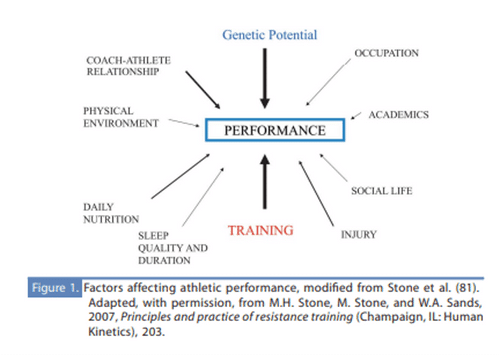

Organizations that have implemented a more collaborative model have seen great success. A report issued by the Australian Institute of Sport (AIS) on training load listed 10 factors that contribute to athlete performance, as shown in the graphic below. As such, specialists across all disciplines at the AIS work together to balance athletes’ acute and chronic loads. “Effective planning can be enhanced by an interdisciplinary approach that is led by the coach of the program with collaboration from the performance support team,” the reports’ authors stated. This allows “the collective expertise and experience of the coach, athlete and performance support team members” to be combined.[iv]

In another article, Wayne Goldsmith asserted that, “There is no doubt that successful sports performance is multi-disciplinary in nature.” Explaining this statement, he wrote: “Athletes and coaches need to be aware of the physiological, biomechanical, psychological, nutritional, medical and immunological and other issues that can impact on their competition performances. It is when all these factors come together and work as an integrated performance system that excellence in high performance sport is possible.”[v]

An athlete management system like Smartabase helps practitioners in each of these areas collect, analyze, visualize, and communicate pertinent information that underpins sound decision-. As sports scientist Chris Petrie wrote, “Allowing us to store access and analyse the data we collect, databases are the most powerful tool in data science, because they consider all the data collect and not individual sources.”[vi] To take this idea a little further, a database that is used correctly not only unites different data types but can also foster greater collaboration between various sports science specialties.

A paper published in the International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance states that “sport scientists can contribute to the success of these organizations by promoting decision support services that incorporates data collection, analysis and communication.” The author goes on to state that success is achieved when data is managed collaboratively and performance staff “build meaningful relationships with key personnel across the organization.”[vii]

ASKING QUESTIONS VS. LOOKING FOR THEM

Another issue that’s preventing teams from tapping into the full potential of athlete data management is that they choose the wrong point in the process to ask and answer questions. With the newfound ability to capture information on everything from acute and chronic load to velocity to sleep quality (and much more), performance staff have access to a greater quantity of data than ever before. But it’s not the amount of gigabytes accumulated, the sheer number of data points, or the hype around a new wearable technology that provides an edge. Rather, the key is the ability to zero in on exactly the right information at the correct time, and then to interpret it in context so it can be acted upon to make better performance and wellness-related decisions.

Instead of looking at current and historical data and using it to prompt questions that require a deeper dive to answer, coaches would be better off assessing their team’s current challenges and opportunities for improvement and using these to drive the creation of specific questions. Then they can refine the number of data sets to create a short list of those that are most relevant, before beginning to look at how the metrics can address such questions. Once they have the answers, or at least clues to what the answers might be, then they can start to adapt and adjust athletes’ training and recovery plans to find better solutions to the team’s most pressing problems.

Often the greatest potential improvements can be found not in the first question but in those that follow it in a logical progression. So for example, a coach might ask his or her team’s performance specialist, “What was our most common injury this past season?” The practitioner goes away, looks at the information in the athlete management system, and tells the coach that knee injuries were the most prevalent injury within the squad.

If that’s the end point, it hasn’t really yielded any actionable information. But if the initial answer prompts the coach or performance staff to ask a series of follow-up questions, the team can get closer to establishing a causal relationship between certain kinds of training, specific times in the competitive calendar, and the incidence of this particular type of injury. Such questions might include, “How many of these were contact and non-contact knee injuries?”, “How many players hurt their knees during the preseason versus the regular season and offseason?”, and “What were we doing in the weight room and on the field when most of the knee injuries occurred?”

ASSESSING READINESS

In addition to obtaining answers from objective data, questions like these can also lead to looking at subjective information that athletes provide through a self-assessment platform like Smartabase Kiosk or the Smartabase Athlete App. This could include daily readiness surveys, sleep quality, and so on. When combined with quantitative information, these insights can start to form a more complete picture of what’s working well, what’s not, and how a team can modify its approach to better prepare athletes for the rigors of competitive play.

Athlete data analysis doesn’t have to be restricted to what has happened and why but can also be applied to improve current, day-to-day team preparation. In this case, a common question that a sports science group might want to answer is, “Are my players ready to train at full speed today?” To provide an accurate answer, there are multiple factors to take into consideration. The first additional question to ask is, “Are they well-rested?”

Once a sports scientist has ticked this box after looking at sleep data, we now need to know if the athletes are ready from a neuromuscular perspective. This can be assessed by having them use a jump/force plate and comparing today’s numbers with historical data to see if their central nervous system has recovered from previous games and training sessions. The details of the preceding training block can also be taken into account.

Now the staff has a 360-degree view of athlete readiness and can either go ahead with the planned training or scale back the intensity and volume of the session, based on the findings from objective and subjective data sets. Rather than keeping data and the people who have access to it in divided silos, such an emergent or collaborative method pulls pertinent information from various disciplines and combines it with the experience and knowledge of the performance and coaching teams to make more informed, collaborative, and timely decisions.

Ultimately, the duty of sports science practitioners is to adequately prepare players for the demands of practice and competition so that they can perform to their full potential while staying safe and healthy. There might not be a magic bullet on this front, but asking better questions as part of a multidisciplinary approach provides a solid starting point for the next phase of effective athlete data management.

About the Author

Dan Duffield | Sport Science Consultant | Fusion Sport

Dan is a University of Queensland graduate with a degree in Exercise and Sports Science. Following the completion of his degree, Dan joined Fusion Sport as a Sports Scientist and has been with the company for 8 years. While working primarily in Australian Sport, Dan spent 18 months working in the UK/EU market and most recently in the US market. Dan has experience implementing Smartabase in various departments and levels of the sport, military, academia and performing arts industries.

Experience true data aggregation with the Smartabase Human Performance Platform.

References and resources:

[i] Patrick Lencioni, Silos, Politics and Turf Wars (San Francisco: Jossey Bass, 2006), 12.

[ii] Robert H. Stewart, “Organizational Silos Within NCAA Division I Athletic Departments,” University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, March 2014, available online at https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/210603211.pdf.

[iii] Wayne Goldsmith, “Performance Science: Integrated Sports Science,” Sports Performance Science, November 8, 2010, available online at http://sportsperformancescience.blogspot.com/2010/11/performance-science-integrated-sports.html.

[iv] “Considerations of Training Load in Relation to Loading and Unloading Phases of Training,” Australian Institute of Sport, May 2020, available online at https://www.ais.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/734363/Considerations-of-training-load.pdf.

[v] Wayne Goldsmith, “Multi-Disciplinary (Performance) Sports Science: The Future of High Performance Sport,” WG Coaching, available online at https://wgcoaching.com/multi-disciplinary-performance-sports-science-the-future-of-high-performance-sport/.

[vi] Chris Petrie, “Data in Sport – Part One,” March 3, 2016, available online at https://thatsportscienceblog.wordpress.com/2016/03/03/data-in-sport/#more-137.

[vii] Patrick Ward, Johann Windt, and Thomas Kempton, “Business Intelligence: How Sport Scientists Can Support Organisation Decision Making in Professional Sport,” International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, January 2019, available online at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330770214_Business_Intelligence_How_Sport_Scientists_Can_Support_Organisation_Decision_Making_in_Professional_Sport.